Authors: Anthea Chloe Pillay, Zahra Okba

2.2. Ocean colour remote sensing and its application#

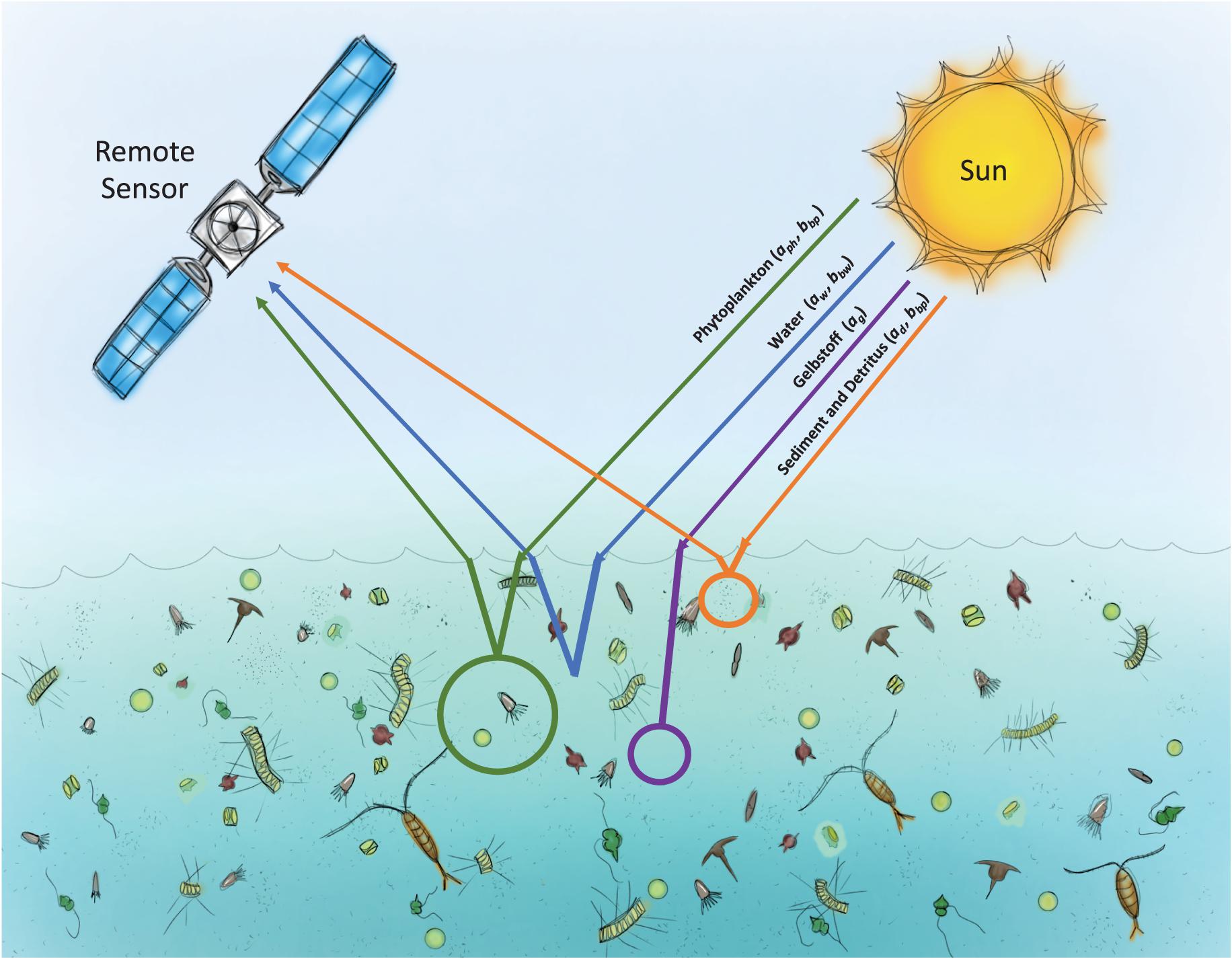

Ocean colour remote sensing has been used as a tool in assessing the “health” of the ocean by means of measuring the chlorophyll-a in phytoplankton through optical sensors (Figure 2.1). The influence of chlorophyll-a on the changes of oceanic colour can provide the level of chlorophyll contained in the water, and thus can allow the estimation of primary productivity. On the other hand, the colour change due to coloured dissolved organic matter (CDOM) may be indicative of pollution and higher particulate matter, particularly in the coastal regions where there is high complexity due to interactions of different natural and anthropogenic phenomena [Teodoro, 2016, Gholizadeh et al., 2016]. It is simpler to estimate primary production in the open ocean as the signal is primarily dependent on phytoplankton along with its associated detrital and CDOM [Groom et al., 2019]. In contrast, coastal waters have additional influences of resuspended particulates, or river run-off which contain CDOM that is independent of that particular phytoplankton assemblage, making these environments more complex to assess optically [IOCCG, 2000].

Fig. 2.1 Ocean colour remote sensing involves the use of satellite detection of spectral variations in the water leaving radiance (or reflectance), whereby the sunlight that has penetrated the water column and then backscattered out to the satellite (Source: Menden-Deuer et al. [2021])#

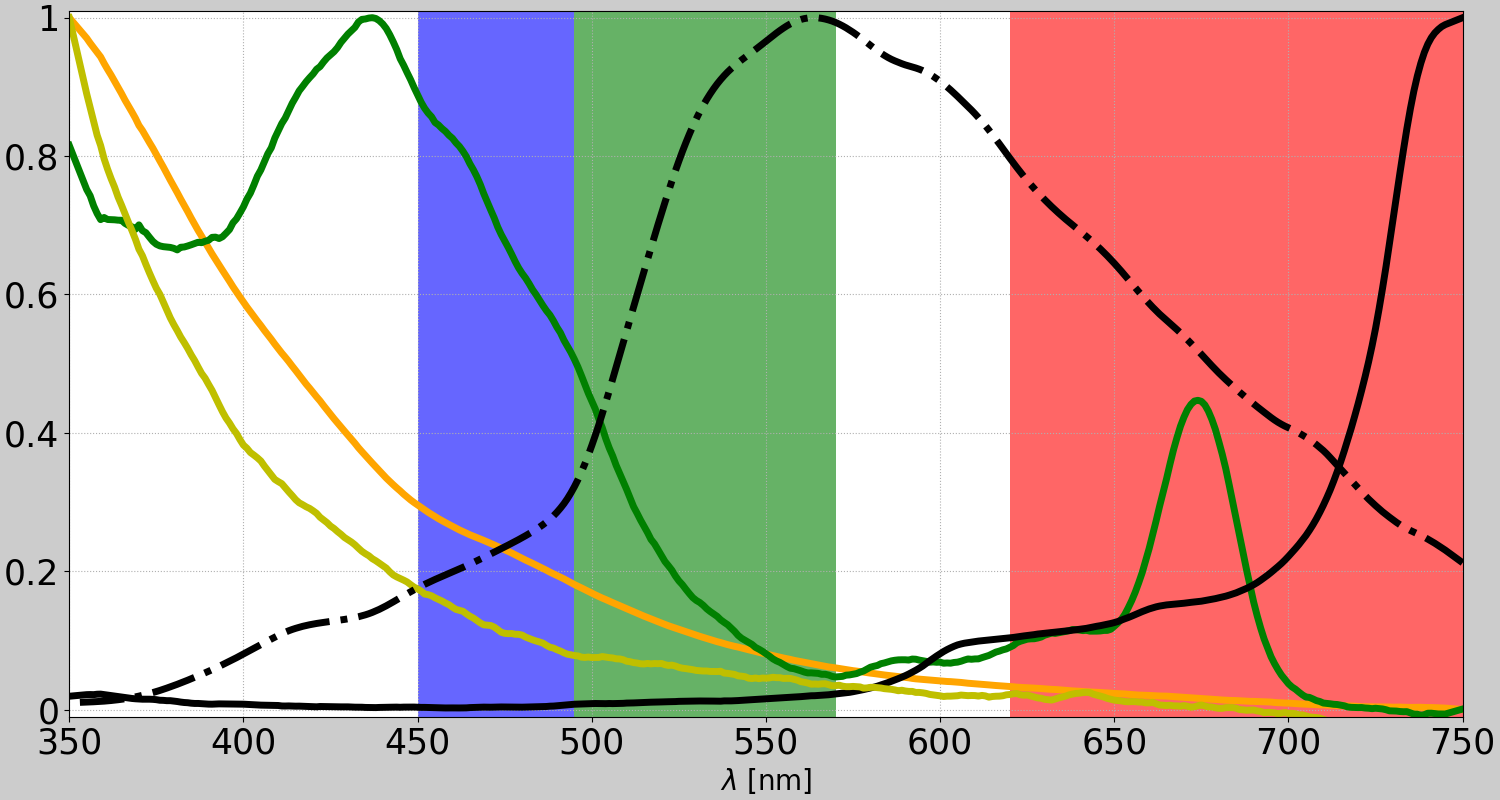

Overall, from an ocean colour point of view, the target is to accurately measure the water leaving radiance in order to relate this to water constituents. Different water constituents absorb and reflect light selectively. The reflected light, which is detected by optical sensors, is influenced by water itself and various optically active water constituents (Figure 2.2), i.e., chlorophyll-a, CDOM, suspended particles [IOCCG, 2000] as mentioned above. To quantify these parameters, in ocean colour remote sensing the fundamental parameter is remote sensing reflectance (Rrs). This is a relative measure of the water leaving radiance to the total incident light. This ratio is then applied in inversion models that estimate water constituents, such as chlorophyll-a [O'Reilly and Werdell, 2019]. It is worth noting that since the CDOM and non-algal particles have a similar functional characteristic [Babin et al., 2003], these parameters are often estimated as the sum of the two [Lee et al., 2002]. A gentle introduction to ocean colour remote sensing is further given in Chapter 3.

Fig. 2.2 An example of light absorption of pure water and of different water constituents, i.e., chlorophyll-a, CDOM, non-algal particles as measured from in-situ water samples along with the measured remote sensing reflectance, all in relative units, in the Japan Sea. The chlorophyll-a concentration was about xx mg m^-3 in waters with xxx m depth. Note that pure water strongly absorbs light in the red bands but has almost zero absorption in the blue-green. Also note that the reflectance is maximum at green where all parameters exhibit low absorption. Source: Eligio Maure.#

As already mentioned above, coastal water quality can be monitored using earth observation as a tool for coastal area management like the deterioration of the coastal habitats by deforestation of mangroves. An effective low-cost ecological indicator is provided by remote sensing of ocean colour and can be continuously and operationally applied in ecosystem-based management [Ahmad, 2019]. These indicators help characterise ecosystem change following disturbance by natural or anthropogenic causes.

Listed below are a few examples that ocean colour remote sensing data can be used for [Ahmad, 2019, Goes et al., 2014, Yang et al., 2018, Maúre et al., 2021]:

Identifying marine reserves and endangered species habitats.

Identifying potential fishing grounds allowing fishermen to work more efficiently and save fuel. This is certainly not intended to encourage overfishing, but rather to provide practical methods for sustainable management and cheaper harvesting.

Monitoring harmful algal blooms (HABs) and tracking their development, spread, and fate, in turn supporting the tourism and aquaculture industries.

Identifying coastal eutrophication potential and aid in monitoring programmes, adaptive management, and decision-making.